A little online research awarded us the opportunity to rent the last and least expensive 4×4 to be had. There was no extra charge to pick it up the evening prior, so we made the short walk along a street of packed earth mixed with a small ration of crushed stone. After a quick walk around to assess and inventory the multitude of scratches scrapes and bruises that marred the outside of the 15-year old Wrangler, papers were signed and she was all mine! Well, at least for the next 24 hours.

The gentleman at the rental company assured us that this was “the most capable of the jeeps in their fleet,” and would take us “anywhere we might want to go.” He added that it had, in fact, started its life as his personal off-road vehicle tricked out to take on the many forest roads and treacherous passes that crisscrossed these mountains. If that were ever the case, its overlanding glory days were certainly behind it now. As we rolled along, the term “rattle trap” came to mind, as we sounded less like a capable 4×4 and more like a toppled-over bucket of bolts rolling around the bed of a vintage pickup.

The idea that I could fish for a month and never below about 10,000 feet had me feeling like a kid in a candy store—

with a pocketful of pennies.

The next morning, a cooler filled, day packs and fly rod tube stashed behind the seats, we climbed aboard our rickety rig to trek to the tundra. Alpine tundra, that is. The minute we chose Colorado for our escape from the fiery furnace that is Texas Hill Country in August, I began to research both popular and off-the-beaten-path fly fishing destinations in that area of the San Juans. I soon discovered that the possibilities are quite nearly endless. There are more trout rivers and streams within a 50-mile radius than I wager could be fished in a lifetime. But there was a particular gem that had caught my attention, sending it to the top of my must-fish list.

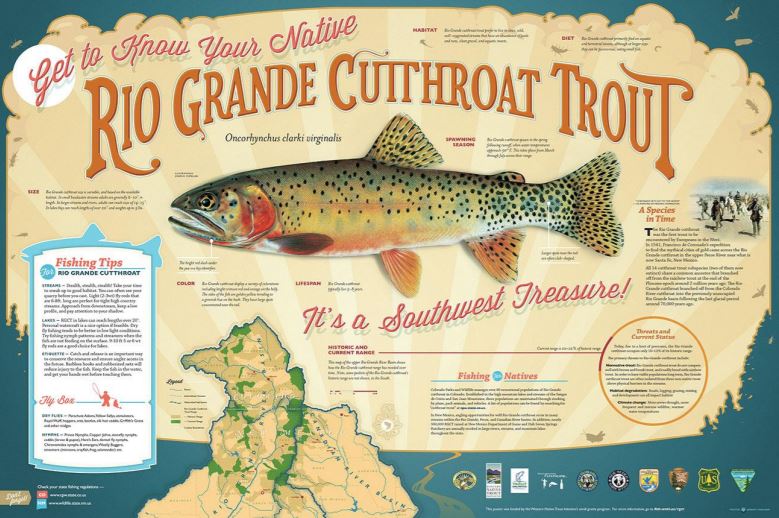

The idea that I could fish for a month and never below about 10,000 feet had me feeling like a kid in a candy store—with a pocketful of pennies. This time, I would be in search of of native Rio Grande Cutthroat Trout in the tributaries of the Rio Grande. It is one of 14 subspecies of cutthroat trout native to the western United States. Cutthroat trout were the first New World trout encountered by Europeans when in 1541, Spanish explorer Francisco de Coronado recorded seeing trout in the Pecos River near Santa Fe, NM. These were most likely Rio Grande cutthroat trout.

Historically, these fish occupied all cool waters in the Rio Grande drainage, including the Chama, Jemez, and Rio San Jose drainages, along with suitable waters of the Pecos and Canadian drainages. But they currently live in only about 100 headwater streams, occupying a mere 10 percent of their former range. Targeting these trout on the fly in their stunningly gorgeous native range is an experience so amazing that the mere idea of it travels down from your brain and flutters around a little in your chest. This sort of excursion borders on Holy pilgrimage to me. So, naturally, I approach it with a good measure of reverence to accompany the excitement. Come to think of it, reverence is often a posture I take when exploring outdoors.

Most of the forest roads and offroad trails in these parts were originally narrow tracks cut through the mountains to ferry supplies and minerals to and from the thousands of mines that pierced these slopes starting in the late 1800s. They were first designed for pack animals and eventually “improved” to accommodate wagons. Early in the 20th Century, the first automobile made its way over one of the more famous passes in the area…but not without the help of a strong team of plow horses. Most have now been acquired by the US Forest Service and are maintained for backcountry access and recreational use. Rough as they can be, without this “maintenance,” they would likely be impassable without it. And depending on snowpack, these routes are usually only open from Late June to early October each year and require a high-clearance 4×4 or OHV (Off-Highway Vehicle) to traverse.

As we headed out of town, though I’m not sure my passenger would have agreed, I felt like I was getting a better feel for the rhythm of the clutch. Most of my fly fishing excursions are solo but for the rare occasion when schedules align and the pursuit takes me to a destination with an unmistakable allure of its own. As was the case here. The route was slow and the climb a little nerve-wracking. The steep switchbacks of loose stone and occasional boulder between us and treeline where pine forest gave way to rolling tundra were often narrow and provided a dizzying view of dropoff out the passenger side window.

At one point, we caught up with a newer model Landrover in deep navy with blacked-out windows, street tires, and shiny chrome wheels. I had the passing thought that it seemed odd to take a luxury sled over such punishing terrain. But there was little time to dwell on it as the driver stopped just past the intersection of a hairpin turn to the left and yet another trail to the right. Since the Rover had stopped just past the right turn, probably to check the map, we were forced to go left and then stop ourselves to consult the map, only to learn that left was the wrong direction.

In retrospect, it was not the best place to pause when only my tenuous ability to keep some gear teeth and a flywheel sufficiently connected stood between survival and a neutral-inspired roll to a backward freefall off the mountainside. This was certainly not a situation suited for clutch-slipping. It didn’t help that two nights prior, no joke, I had dreamed I rolled backward off of a cliff in a car I was driving…complete with that tingly, stomach-churning feeling of falling. But with some patience and very slow and deliberate operation of the vehicle, we had backed safely around the tight corner and were again headed in the right direction. Up and over.

I don’t have suitable words for the relief that came as we emerged, rocky climb behind us, onto the vast expanse of green. As we reached the highest point of the pass, our breath was quickened, not just by the views, but by the thinning air well above 12,000 feet. We pulled the 4×4 off of the main trail to take a break and soak up the views from what felt, to us, like the top of the world.

It might have been easy to think we were all alone up there if not for the occasional sharp and loud “eeking” sound made, as we would discover, by one of the locals. I kept hearing this sound…almost like the chirp of a chipmunk, but much fuller and significantly louder as it echoed off of the slopes & boulders strewn across the high mountain basin. No, we were not alone.

Finally, I laid eyes on one of our watchful neighbors. A fat little marmot…rather like a beaver without tail or teeth, standing sentinel on top of a rock pile and intent on alerting the whole neighborhood of our presence. A scan of our surroundings, eyes tuned to the sight of little brown blurs of movement, revealed that we were, indeed, surrounded. Since that experience, I now seek out situations where it’s just me and the marmots. They live in some beautifully remote places.

Back in our chariot of glass steel, we started our descent on the opposite side, I heard water before I saw it. The top was down and as we rounded a bend in the road about 500 feet or so lower in elevation, and I heard the unmistakable gurgle of flowing water prick my ears. Looking down, I saw what amounted to a trickle running down from the left, through a small pipe pretending to be a culvert, and exiting to the right and on down the shallow swale.

I was witnessing the birth of a river. Every trickle that forms and begins to flow down a mountainside, save those destined for an alpine lake, is bound, directly or indirectly, to become a river. And something about the potential, the idea that a river was simultaneously beginning here and ending elsewhere, brought a mix of thrill and emotion similar to what I experienced the first time I saw the Grand Canyon. It’s that thing that happens when you allow yourself to feel small in all of the best ways. To feel as though you are a part of something greater, a minute yet imperative piece of the perfection of creation.

We continued our progress along the roadway as the little-ditch-that-could meandered closer and farther from us, growing up into a proper, fishable creek. It was hard to guess how far upstream trout would be present, so when I felt like the water was sufficient enough to hold sizable natives, we pulled off at the next level and clear spot along the road. To tell the truth, I wasn’t even sure if trout WERE present here. I was going on mapless recommendations and rumors. You see, local fly anglers don’t generally share much more than vicinity when suggesting areas to fish. But I was too excited and determined to even entertain failure. If there were native Rios here, I thought, this little 4wt and I were going to find them.

Fly rods, like acquaintances, come and go over time. But some become good friends bound to stick around. The beauty I brought along for this excursion was chosen with no shortage of sentiment. The 8ft, 4wt Orvis Superfine in tow, a birthday present several years ago, first introduced me to the zen of fly casting. Though I had fished with it all over the country by this point, it had never been bent on a trout. And since it was designed for situations precisely like the one I was headed for, it seemed only fair to provide an opportunity for it to excel at its intended purpose. And it was about to shine.

Out of the Jeep, I hastily assembled and strung up my rod, stepped into my wet wading socks, and donned my Fishpond “Tenderfoot” Youth fishing vest. It’s the only respectable vest I’ve ever found that is small enough to fit me. Because evidently, when fly fishing vest designers sleep, they “dream of large women.” (Extra points if you can name that movie.) Anyhow, once properly outfitted, I bounded down the hill as a kid headed for the swimming hole for the first dip of summer.

Once streamside, I mustered enough discipline to stop and read the water looking for deeper sections along cut banks or behind the occasional boulder where trout might hold. No guessing was necessary in this case as the clear water and slower flow made it as though I was viewing fish floating suspended under glass. Two-way glass. So I snuck across and came up alongside to deliver my first cast at the head of a run. A full-flexing fly rod was purpose-built to deliver a fly with all of the delicacy pristine water demands, and the Orvis Superfine is among the classics in this category. If the topwater strike wasn’t immediate, it was just shy. A rather quick strip in had a gorgeous Rio Cuttie hanging out in the bottom of my net.

The paint job on these fish is otherworldly, and that signature slash of orange along the lower jaw leaves little question that they are aptly named. First catch in the net, I went on to spend a few of the most enjoyable hours fly fishing in recent memory. It became almost comical to me. Nearly every cast, every drift, was rewarded with a topwater splash and subsequent tug at the tippet. These waters are covered with ice and snow for all but a fleeting stretch of summer, and the vigor with which the trout feed at higher altitude signals that they are well aware of this fact.

Eventually, the reality of a waning day and long haul back over the pass and down the mountain to civilization came knocking at the door of my little paradise. On the way out, we ran into our Land-roving friend again, a local gentleman and fly angler who had brought his visiting son to fish these holy waters. A nice chap who volunteered a few other location suggestions to a fellow creek stomper.

The slow crawl back down the mountain in 4 lo gave ample time to reflect on an afternoon well spent—to relive some of those drifts. Particularly the last one made around and behind a certain boulder. At no more than 2 feet, it was still one of the deeper pools in the stretch I was fishing, meaning there was a good chance it might hold one of the larger fish likely to inhabit these waters. I had already missed the snag on a few takes in the current. My luck was surely running out, but I still felt there was a chance at a hookup.

I inspected and dried my fly, reapplying a squeeze of floatant to keep it high on the water. Making a couple of false casts, I slipped a little more line to start my drift further upstream. That was the ticket. With a convincing gulp, the fly disappeared below the surface, the line tightened on the head shake of a sizeable Rio Grande Cutthroat. And with that, the day’s biggest catch appeared at the bottom of my net.

I will seek out opportunities to return to waters like these as often as possible. To mingle with the marmots. To breathe in the high mountain air. To once again pass a little time casting in the clouds.

There’s a long list of things I love about fly fishing. And the way wade fishing small water serves to anchor me in the moment certainly ranks high. I’ve been thinking quite a bit lately about those fleeting moments in life when you are totally present and in some relative state of bliss. Those times are so precious, and in this day and age, fairly hard to come by without a little impetus. So I say make plans to chase them. And when you catch one, embrace it. One might just take you to the top of the world.